- Home

- Dogo Barry Graham

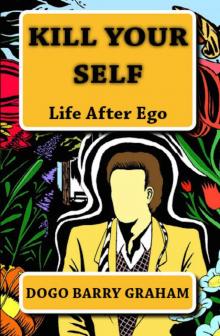

Kill Your Self

Kill Your Self Read online

Kill Your Self: Life After Ego

Dogo Barry Graham

Published by Cracked Sidewalk Press, 2011.

While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein.

KILL YOUR SELF: LIFE AFTER EGO

First edition. September 27, 2011.

Copyright © 2011 Dogo Barry Graham.

Written by Dogo Barry Graham.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

AUTHOR’S NOTE

THREE USEFUL GUIDELINES FOR ZEN PRACTICE

INTRODUCTION: THE LOUD, FAT PERSON IN FRONT OF YOU

WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE?

WHAT THIS BOOK CANNOT DO FOR YOU

ARRIVING WHERE YOU ARE

ONLY SUFFERING

GET YOUR SELF OUT OF YOUR WAY

READING YOURSELF AS A MAP

LEAVE YOUR RELATIONSHIP

THE ANTIDOTE FOR HATE

NO TRANSFORMATION

THE EMPTY BOAT

AT HOME IN HELL

KARMA IS NOT A BITCH

THE KARMA OF LONELINESS

NO ONE IS BORN, SO NO ONE IS BORN AGAIN

EVERY BELIEF IS WRONG: A TALK AND DISCUSSION

THE MOST INTIMATE

ORDINARY PERFECTION

WHO HATES WHAT LIFE?

GRATITUDE

THE MONSTER IS COMING TO GET US

ZEN AND DEPRESSION

ZEN IN THE STREET

COMPASSIONATE DETACHMENT

DELIBERATE MARTYRDOM IS SELF-CENTERED

A LEASH AROUND YOUR NECK

THE COIN LOST IN THE RIVER

JUST SEE WHAT HAPPENS

DEMON

NO OBSTACLES

EAT THE FINGER

MEDITATION ISN’T ENTERTAINMENT (EXCEPT WHEN IT IS)

THE SPACE IN BETWEEN

GO HOME

GAP

NO RIGHTEOUS ANGER

OBSERVING

WHAT DO YOU WANT?

NO SILENCE, NO RETREAT

ANGRY

IDENTIFYING AS UNIDENTIFIED

TEACH A MAN TO FISH

VIOLENCE HAS NO SUBTEXT

IF YOU LIKE CHOCOLATE IN SAMSARA, YOU’LL LIKE IT JUST AS MUCH IN NIRVANA

ONE THING AND ANOTHER

NOT AN ANSWER, ONLY A REPLY

ARE YOU AT WAR?

SUPERMAN ISN’T COMING

ARE YOU READY?

NO PAST, NO FUTURE

THE MIDDLE WAY

CUTTING INTO ONE

MOVING

WRONG QUESTIONS

THE PRESENT MOMENT

MARA’S FAVORITE THING

IS MARA REAL?

TELL IT TO THE JUDGE

NOTHING IS BORING

THE CERTAINTY OF SUN AND MOON

BEING RIGHT

ON THE JOB

HEARTBROKEN

TAKING CARE OF THE BODY OF THE BUDDHA

THE BODY OF THE BUDDHA, TOSSED IN THE GARBAGE

BUDDHA MADE OF STONE, BUDDHA MADE OF SPACE

BEING DEAD IS THE BEST WAY TO LIVE

A REQUEST FROM THE AUTHOR

About the Author

This book is dedicated to the memory

of the great master

Charlotte Joko Beck

with love and gratitude

in word and action

and beyond word or action

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Most books are written. This is true of the novels I have had published. But this is a book that happened rather than was written. It arose from unscripted Dharma talks given at The Sitting Frog Zen Center in Phoenix, AZ, and from articles and blog posts, and, most of all, from answers to questions asked by my Zen students. It had begun happening long before I ever considered it as a book.

I am grateful to Dan Hoen Hull, Jiryu Ryan Garris, Gina Madrid, Jikai Lonna Kelley, Kwan Mi Cecily Dubusker, Doin John Hinton, Rengetsu Kathleen Clark, Stephen Gay, Larry Fondation, Kathy Hayes, Nick Hentoff, M.V. Moorhead, Vince Larue, John Tarrant, Alisa Ware Garris, Philip Ryan, Deb Saint, John Scudder, Kyle Niemier, Megan Farley, Ango Neil Heidrich, Brother Ron Fender, Stefanie Harvey, Patrick Millikin, Gerry Loose, Liz Fox, Susan Thompson, Kyle Smith, and Laura Urquhart, all of whom have helped with this book, some in ways they do not know.

I am especially grateful to Daishin Bree Stephenson, for everything, always.

This book would not have come into being without the encouragement of the late Charlotte Joko Beck, whose kindness to me and to my students was and is a priceless treasure.

Dogo Barry Graham

Sitting Frog Zen Center

Phoenix, AZ

Autumn, Year of the Hare

THREE USEFUL GUIDELINES FOR ZEN PRACTICE

1. Trust yourself.

2. Don’t make it about yourself.

3. Don’t make it about anyone or anything else, either.

INTRODUCTION: THE LOUD, FAT PERSON IN FRONT OF YOU

Imagine you’re at a movie, and the person sitting in front of you is so huge and fat you can’t see the screen because he’s completely blocking your view. He’s also talking loudly, so you can’t hear the movie.

That person is you. You can’t see the perfection of your life, as it is right now, because you’re in your own way.

Here is how I got out of my own way:

Decades ago, I walked into a small Zen center in a rough neighborhood of an industrial city. It was barely even a Zen Center; the teacher, a retired steelworker who shook with Parkinson’s Disease, held services in his apartment.

I went there because I didn’t have a better idea. I knew I was heading for prison or the morgue. I had friends in both places, and I desired neither. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder.

Only two other people would show up at the Zen center that evening, but I was early, and there was only the teacher. I told him everything that was wrong with me, and asked him, “Can you help me?”

“No,” he said.

I thought he meant he didn’t have enough training, wasn’t advanced enough—maybe wasn’t enlightened enough. “Well, who can help me?” I asked.

“Nobody,” he said. “You’ll never be any better than you are now. Anything you have to deal with now, you’ll have to deal with for the rest of your life.”

“So why should I bother with Zen?”

“I don’t know. I never said you should. You came here.”

“Well, do you think I should?”

“How would I know? You’re welcome to if you want to. It’s none of my business. But if you practice here, you’re responsible for yourself.”

When I look at these words in print, they seem harsh, uncaring. They were anything but. Hearing them, I felt an almost overwhelming sense of relief. I knew I was being leveled with. I wasn’t being lied to, and so, even though I couldn’t understand why anyone would practice Zen if it wasn’t going to “help” them, I trusted it and I trusted him. So, when the other two participants that evening showed up, I joined in the service. We sat on cushions, chanted in Japanese, and then spent two half-hour periods in silent, objectless meditation called zazen.

Zazen means “sitting in meditation.” It is the heart of Zen practice, and should be done daily. It is best learned from a teacher, who can check your posture and answer questions, but here are the basics of the practice that Dogen Zenji calls “the Dharma gate of great ease and joy:”

Sit on the edge of your zafu (cushion). Your knees should rest on your zabuton (mat), so that your weight is distributed between three points—your bo

ttom, and each knee.

Imagine that there are wheels on your pelvis, like the wheels on a shopping cart. Roll the wheels forward, and you will feel your body come into alignment.

Your posture should now be upright and strong, but relaxed. Align your head so that the ceiling could rest on your crown if it were low enough. Place your hands in Cosmic Mudra—just below your navel, palms up, left palm on top of right palm, thumb tips touching.

Half-close your eyes, letting them go out of focus. Breathe naturally through your nose, not trying to control your breathing. Just observe the breath, at the point where you feel it enter. (In your first few months of practice, you might find it useful to count each breath, starting over again when you get distracted or when you reach the count of ten. I’ve never reached the count of ten.) When thoughts arise, don’t fight them and don’t welcome them; just acknowledge them and return your attention to the breath. Don’t tell yourself a story; when a story starts, just acknowledge it and return to the breath. Don’t aim for any state, tranquil or angry. When you realize you feel angry, don’t try to stop being angry, and don’t get into the anger; just acknowledge it and return to the breath. When you realize you feel tranquil, don’t get into the tranquility; just acknowledge it and return to the breath. Ecstatic, agitated, calm, impatient, bored, rapturous—whatever comes up, just acknowledge it and return to the breath. To return to the breath is to return to life, your life, this moment.

I thought it was the weirdest, stupidest, most pointless thing I could imagine. And I knew I was going to keep on doing it, and that it was going to save my life.

It did.

Two decades later, I’m still doing it, and it’s still saving my life. I teach it, and I see it saving other lives.

Although my childhood and adolescence were an almost constant hell—a hell that has scarred me in ways I expect will never fully heal—I am grateful for that hell.

I am grateful for it because it made my life unbearable. As an adult, I was so brutalized by my experiences growing up that I was barely able to function. I brought misery to myself and to others. I deeply regret the latter, but am grateful for the former.

Why would anyone be grateful for more than 20 years of misery? Because it forced me to take responsibility for my own happiness.

There came a point at which I’d simply had enough. I was sick of hurting others. I was sick of hurting myself. I was sick of myself—or, rather, I was sick of my self. I was sick of the conditioned self, the bundle of preferences, fears, rages, hatreds. I knew I didn’t want to live the life I was living. I knew I didn’t want to be the cruel, small, abusive person I was. But I still lived that life and I still was that person. I was locked inside that life and that person, and, despite my best intentions, I couldn’t get out.

Then I found myself at the Zen Center.

To follow the Buddha Way is sometimes to walk through hell wearing a gasoline suit. We bear witness to everything that arises, good or bad, and we don’t cling to the good or turn away from the bad. Most people don’t do it, because their lives never become so utterly unbearable that they have to do something about it. So, without a practice, they live their lives in a constant state of dissatisfaction. They read books, they philosophize, they turn towards gurus—religious and secular—all of whom are selling the same snake oil. They look to other people to make them happy.

Wherever they look for happiness, they never find it. Over and over, they experience a rush of excitement about the latest lover or guru or book or therapy, and then it wears off and they are let down. They live a life of quiet (or not so quiet) desperation, and then they die, as Thoreau put it, never having actually lived.

This is why I am grateful to the parents who didn’t want me, grateful to all those who abused me as a child and teenager, grateful for every kick or punch I took, grateful to everyone who spat on me.

Because they damaged me so badly that I couldn’t bear life as I was living it. And so I turned to the practice of Zen, and something happened to me that doesn’t seem to happen to many people.

I became happy.

My pain didn’t vanish. My fear, my anger, all the accumulated poison, was still with me, and always will be. But it ceased to matter.

I am cruel, stupid, intolerant, cowardly and weak. So I am grateful for the gift of misery that forced me to take responsibility for the cessation of the suffering I was perpetuating, the misery that sent me to the Zen center. Otherwise, I might never have followed this practice that let me see through the illusion of my conditioned self, see the reality of the person who was always there, the person I always was: the Buddha. Perfect, complete, lacking nothing.

Recently, I’ve found myself pondering the question, “Is Zen enough?” The Zen world contains as many angry, unhappy, ego-driven people as the corporate world (and, I suspect, more). Some of those people have identified as Zen practitioners for decades, and yet they’re still miserable. In that light, how can Zen be enough?

It would be enough if those people were actually practicing Zen, but they’re not. There’s not much Zen practice going on anywhere, especially in Zen centers. There’s not much spiritual practice going on anywhere, especially in churches, temples, monasteries and ashrams. Instead of sincerely practicing, letting go of egoic view, closing the imaginary gap between self and other, subject and object, most people are caught up in their own little story, their own grasping, their own attacking, their own defending. There are people who practice living outside of story, practice not grasping and not attacking and not defending, because they know that there is nothing to grasp, and no one to attack or defend. They are practicing Zen.

To be happy, to be free, to stop causing harmful karma, you have to let go of the mind that seeks, desires and avoids. That doesn’t mean that the seeking, desiring, avoiding mind disappears; it’s still there, but it has no power, because you no longer identify with it. When you get what you want, you’re happy and thankful. When you don’t get what you want, you’re happy and thankful. No attachment to heaven, no fear of hell.

It is important to note that the subtitle of this book is Life After Ego. Not without ego. If such a state were possible, it not only wouldn’t alleviate suffering, we wouldn’t know whose shoes to put on in the morning.

One of my Zen students wrote:

Prior to practicing zen, I was an angry, grumbling, arrogant, prideful, quasi-self-secluding troll who adamantly refused to let people close because I was capable of taking care of myself and living life without the help or input of others. I was dedicated to my identity of being hard and cold, of being a private island in the sea of humanity. Did I mention that I was fucking miserable?

The reality is that I am a laid-back, chatty, people-lovin’ hippie, who laughs a lot. The angry troll is still present, but instead of fighting with and berating her, I hold her hand and love her. The ego is not something to be ignored, but to learn from and to acknowledge.

I love her too. In that love, I offer this book. May all beings be happy. May all beings be safe. May all beings be at peace. May all beings be free from suffering and the causes of suffering. May all beings awaken to the light of their true nature.

WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE?

Here is the bad news: It’s not about you.

Here is the good news: It’s not about you.

So many people I meet are like a friend of mine who tells me she doesn’t worry about birth control, “Because I won’t get pregnant if God doesn’t want me to.” Or another friend who said, after his car broke down at the start of a road trip, “I’ll bet there was a snake or something that was going to be there, and it would have bitten me if the Universe hadn’t made the car break down.” Or another friend who thinks his career as a musician is going poorly because God wants him to give it up and get a steady job.

Ah, that explains why there is so much suffering in the world, so much war, so much famine. It’s because the deities are too busy to do anything about it. God is too busy f

ollowing Shelley around the bars of Phoenix, Arizona, making sure she doesn’t get impregnated by any of the men she takes home... and when He’s not doing that, He’s fretting about what Dave ought to be doing for a living. And the Universe is busy sabotaging Joe’s car to keep him from going to places that might be dangerous.

You can call your imaginary parent God, or the Universe, or anything else you want to. It’s not about religion, not about faith – it’s about narcissism. It’s about you, and that’s why you suffer.

The good news is that you don’t have to suffer. You can’t avoid pain, but you can avoid suffering. Because suffering is not caused by pain. It’s caused by taking it personally. It’s caused by your grandiose little ego’s desire to avoid pain.

Are you getting a little bit upset at this point? Getting annoyed at what I’m saying about you? Or maybe you’re thinking, He doesn’t mean me! Well, I do mean you – because if that’s what you’re thinking, you’re taking it personally.

But that personality is not who you are. The thoughts you are having as you read this are not who you are. When you examine who you really are, you might discover that you are your own imaginary friend.

We don’t exist in the way that we think we do. We delude ourselves that he have a fixed, static personality, something that defines us, and many of us think we will continue to exist after we die. Not only can we not exist after we die—we don’t really exist during our lives, at least not in any fixed, unchanging way. Each person is an aggregate of constantly-changing phenomena, and the illusion of continuity is created by memory. Who are you? The person you were five years ago? Ten years ago? The person you’ll be five or ten years from now?

If you’re attached to the idea of yourself as being real, fixed and permanent, you can defend that attachment by pointing to the fact that you have a documented existence of however many years. Well, any river you can name has a documented existence, but that too is an illusion. You can’t put your hand in the same river twice. It has the same name, but it’s not the same water. It’s in constant flow, constant change. So is every person.

Kill Your Self

Kill Your Self